Rethinking social value as a driver for urban prosperity and placemaking

Social value has gained significant traction in public sector procurement in the last decade1. While the focus in Australia and North America has been specific to social and Indigenous procurement, complemented by regulatory and international pressure to address issues of modern slavery and human rights, the UK has been leading the charge on broadening the social value paradigm to encompass strategic and evidence-based approaches to deriving value for society.

In expanding the view from procurement mechanisms and spending power and to consider the role of place, design, management, and operation, the UK has successfully expanded the concept of social value to include the economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of a region—an important shift that encourages a holistic lens and reflects the triple bottom line of sustainability.

The rise in ESG and the four scopes of impact for the built environment

The increased global focus on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) over the past decade has driven a particular emphasis on the importance of the social component of ESG. While this attention has been welcome, there is an implication that social issues are distinct from environmental and governance challenges. This risks a narrowed definition of what the term “social” encapsulates, pigeon-holing it to encompass diversity, equity, and inclusion, when in fact it must be broadened to include the full spectrum of social impact and how it pertains to infrastructure and the built environment.

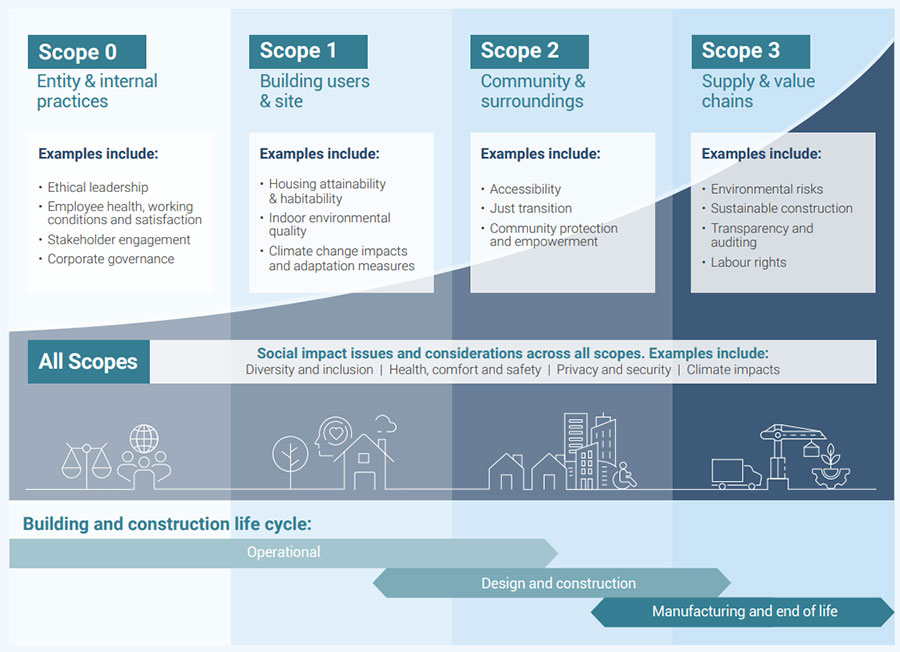

The latest thought leadership in this area shows why we shouldn’t limit the definition of social value. The World Green Building Council’s white paper on Social Impact across the Built Environment borrows from carbon emission scopes to conceptualize a broader set of social impacts, from the immediate realm of corporate governance, to the impact achieved with tenants and end users of the development, to the neighbors and local communities outside of the red line, and more widely through approaches to responsible procurement and supply chain engagement.

Source: Four scopes of social impact for the built environment – LINK

As a result, the private sector is responding with rising levels of adoption and integration of social considerations within corporate strategy and policy.

The emphasis on the social component in ESG has brought increasing interest from the institutional investment and asset management industry, and market leaders in the UK and Europe are now looking to develop in-house toolkits to consolidate the integration of social impact in a range of real asset funds, including impact-led products.

It’s notable that finance-related regulation is also starting to catch up with this rapidly moving social agenda. In Europe, the sustainable finance disclosure regulation has sought to encourage transparency and robustness, while the IFC’s more recent sustainability disclosure requirements in the UK introduce an investment labels regime alongside disclosures and marketing to improve the scrutiny of socially and environmentally sustainable products.

The consolidation of the Taskforce on Social related Financial Disclosure (TSFD) and the Taskforce on Inequality related Financial Disclosure (TIFD) into a single initiative. (TISFD) demonstrates the growing significance of the social agenda. Yet emerging ESG disclosure requirements regulation from the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US will require businesses and ESG fund managers to disclose more about climate-related risks and opportunities, without holistic consideration of wider impacts on people and places. As a result, there remains a significant level of variation in terms of social regulation and requirements, emphasizing the need for standardization in principles, practice, reporting, and measurement.

What’s next?

Amid this complex and fast-moving global agenda, there are some useful lessons to apply from the practical experience of the UK and beyond. Below we have summarized five key messages to watch out for in the international social value and impact space in the coming years.

1. Going beyond the basics.

Using social value as a shallow tick-box exercise for communications purposes no longer works for stakeholders and the wider public. We expect to see more clients seeking to understand the range of impact levers available to them at an organizational and a place-specific level, from the use of social due diligence during transactions, to enhanced social procurement and its management up and down the value chain, through to genuine placemaking that proactively plans for and maximizes the potential for social contribution. This is being developed as clients start to invest in longitudinal studies to track, capture, and manage their impact over time, such as at Wilson Place in Dublin by IPUT Real Estate.

2. The importance of process in scaling up

Rather than showcasing one or two glossy case studies, we anticipate a turn towards truly integrating social impact into everyday operations. Process is key here: by embedding a consistent set of steps throughout sectors, teams, consultants, and partners, social impact is no longer dictated by individuals and becomes a core part of the investment and development life cycle, to be considered alongside financial, economic, and environmental components. For the real assets sector, there is also the question of reporting and assurance as financial disclosure regulation starts to bite and robust data management processes become more important.

3. Joining up the social with local economic objectives

Sophisticated approaches to social impact don’t exist in a vacuum; they’re evidence-based and place-specific, intimately tied to local economic opportunities and needs. We anticipate a drive towards broader and more rigorous place-based needs analysis as the first step in developing meaningful social value and impact plans. One example of embedding the social within economic objectives is the growing recognition of inclusive innovation as a core part of research, development, and innovation-led development.

4. Creating genuine legacy from major projects

As the view of social value expands to include economic drivers, urban prosperity, and placemaking, the focus is shifting towards the long-term legacy of major projects. Clients are now questioning the tangible changes they can deliver for communities.

Our 2018 study on the regeneration of Kings Cross in London highlighted that a flexible approach, placemaking, and long-term stewardship accelerated its transformation into a recognized “place” and outperformed other areas in the London Plan. In Australia, with the 2032 Brisbane Olympics approaching, the scrutiny of public fund use requires a social value lens to ensure an inclusive and accountable legacy

5. Calls for standardization

While environmental standards are well-established, social outcome measurements lack standardization, leading to varied definitions and approaches that hinder comparison.

To address this, we see four key areas for enhanced standardization in the built environment industry:

- Stakeholder engagement. Promote best practices in stakeholder engagement to inform measurement and assessment, as per social value international principles.

- Additionality. Ensure social value and impact are truly additional to “business as usual,” avoiding claims on benefits that would occur regardless.

- Transparency. Social value and impact claims will be increasingly scrutinized and compared. Transparency in approach, assumptions, and limitations will be increasingly expected.

- Proxies. Standardize benchmark and proxy values to withstand scrutiny, while still considering community perspectives and demographic nuances.

At Hatch, we’re broadening how our clients and partners respond to these drivers by understanding social value as a more holistic lens that encapsulates outcomes relating to urban prosperity, quality of life, and placemaking. Contact us to find out more about our social advisory services and how we can support your approach to social impact.

Leigh Holford

Economics Principal, Urban Solutions

Leigh Holford is an Economist and sustainability professional with extensive experience in project planning and delivery in urban and regional development, infrastructure, and the environment. She operates at the intersection of economic and social value with a focus on long-term sustainability outcomes. Leigh has extensive experience working with international institutions, including the World Bank, UN-Habitat, UNCHR, GGGI and the private, public, and charitable sectors to address problems of sustainable and inclusive community development. She has worked across the globe including in Africa, America, Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Australia.