The journey to zero failure: how to connect your organization for resilience

Coping with surprises

The combination of complicated, energy-intensive facilities and fallible human work systems is a recipe for disaster. Safety science researchers identify resilience as a necessity to manage this downside risk.

Surprises come in many forms. Transient events, like an earthquake, triggered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011. These types of black swan events are best mitigated, since prevention strategies (other than not locating nuclear facilities in earthquake zones) are limited. Other transient events, like the current global pandemic, can temporarily shift focus away from proactive planning toward immediate remediation.

The industrial tragedies listed in the introduction are linked less to transient events than to missed trends. The common weakness in many of these examples is the normalization of deviance (Diane Vaughan's term from the Challenger space shuttle disaster investigation)[1]. Other safety researchers simply call it drift.

What is drift and why does it matter to your organization?

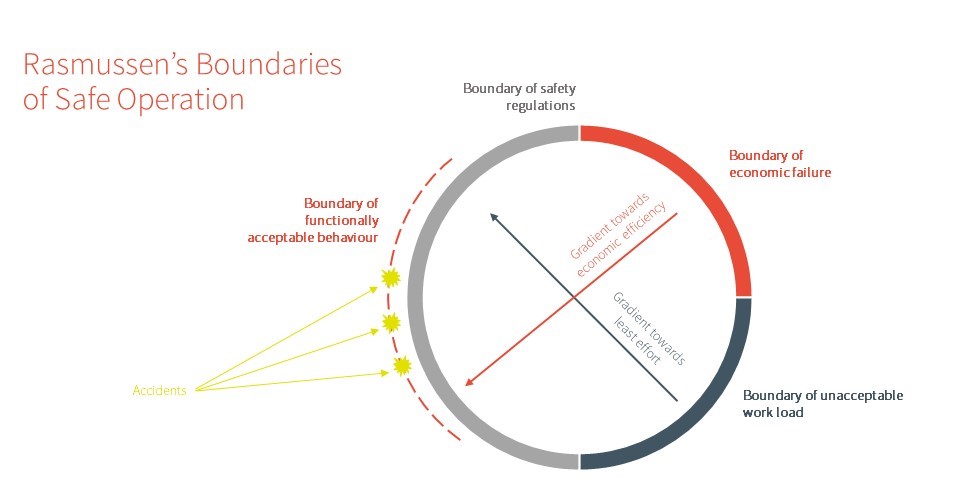

Jens Rasmussen[2] shifted the paradigm in safety science. Instead of obsessing about human error at the front line causing accidents, he expanded the scope to look more broadly at organizational pressures under which work is done.

The need to avoid economic ruin leads to an inexorable drive to contain and reduce costs. Mounting workloads (required by new legislation, etc.) turn workers to finding shortcuts. These unrelenting pressures slowly but surely push work systems toward failure. Drift down efficiency-driven gradients is thus assured.

How do we address drift?

A countervailing effort is required to combat drift. Rasmussen himself identified strong process safety culture as such a countermeasure.

Leaders shape organizational culture. Culture shapes people's behaviors. A positive process safety culture directly addresses drift by acknowledging that people are led, work is managed, and processes are controlled. This contrasts with the more common but noxious view that people, work, and processes all simply need to be controlled.

A well-defined connection between these three elements is needed to invigorate a process safety culture. The human players in the system need to connect to:

- The process intricacies that they influence

- The people in the diverse teams working together

- The purpose of their organization, at local and global levels

Connecting to the process

Process safety is not something an organization starts with. It is not a default position from which human error can drag us toward danger. Process safety is created.

Rasmussen[2] encouraged the owners of process-intensive work systems to make workers aware of the boundaries of safe operation they work within. The easier and less effective alternative is to just declare somewhat arbitrarily increased margins of safety.

"The most promising general approach to improved risk management appears to be an explicit identification of the boundaries of safe operation together with efforts to make these boundaries visible to the actors and to give them an opportunity to learn to cope with these boundaries. In addition to improved safety, making boundaries visible may also increase system effectiveness in that operation close to known boundaries may be safer than requiring excessive margins which are likely to deteriorate in unpredictable ways under pressure." [2]

It's better to understand the nature of the hazards one is dealing with at the "sharp end" of the business. This process safety competencyis a key feature of process safety management systems.

Connecting to other people

Awareness of a worker's role in an intricate, interdependent set of processes allows them to appreciate their contribution to preventing "Swiss cheese" safety breaches due to drift that could contribute to a series of events leading to loss of control.

This increased awareness of inter-dependence (between shifts and with upstream and downstream partners, for instance) can lessen narrow-minded behaviors and lead to a deep appreciation that your success is my success.

This helps cultivate a heart-felt purpose that will enable different players upstream and downstream to see that they share a common cause. It's therefore necessary to measure success in a way that doesn't just optimize for local performance at the expense of overall outcomes.

Connecting with purpose

The organization's purpose must make bold commitments to zero harm in order to connect workers to it in a way that ensures it becomes part of the organizational culture.

An organization's purpose answers the "why": why do we exist, why do we do what we do? Articulating the why takes inspirational language anchored by values. It describes meaningful intentions that people can connect with.

Too many organizations either don't have purpose statements or the statements are nebulous and uninspiring. Think of bland intentions like "maximize shareholder wealth." This blanket statement doesn't help people connect with the values that guide your existence as a company. It simply states an obvious function of all for-profit companies. It doesn't answer the why.

In contrast, a current client is using language such as "sustainable development," "excellence and passion for people and the planet," and "life matters most...do what's right." These purpose statements are affecting and motivating because they're imbued with a set of shared human values that readers can identify with.

Clearly articulating your organization's purpose in this manner also places pressure on business leaders to walk their talk. To truly be effective, workers need to repeatedly see their leaders backing up these aspirations with congruent and tangible actions.

The challenges of creating connection to achieve resilience

In my experience, these are some of the areas that need the most work to enable connection. Here are some ways in which we can enable it:

- The journey to a strong process safety culture needs to be leader-led

- Well-designed work requires considerable attention (think-plan-do-check-act)

- Well-designed work requires compliance and adherence to plans must be diligently managed

- The journey to zero failure is never over since it must striven for every hour of every day

But the rewards of arresting drift that can lead to catastrophe are considerable. We must continually seek ways to improve preparedness and preventative measures in process-intensive industries while remaining adaptable to quickly evolving business landscapes.

With the right approach to process safety we can prevent the shameful headlines of massive industrial disasters. But more importantly, we can save lives and protect our planet. The future of our businesses and our communities depend on it.

References

-

1. Vaughan, Diane (1996). The Challenger launch decision: risky technology, culture, and deviance at NASA. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-85175-4

2. Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Safety Science, 27(2-3), 183-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00052-0